Are you ready for a wild ride on the digital seas? Buckle up and throw on a life jacket because we're diving into the world of ransomware, where cybercriminals are the modern-day pirates taking your valuable data hostage and demanding a ransom!

What is Ransomware?

But what is “ransomware?” I hear you ask. It’s a type of malware (malicious software) that typically encrypts a victim's files and demands payment in exchange for the decryption key to regain access to the files.

Ransomware can be spread through various means, from phishing emails to infected software downloads. It can cause significant financial and operational disruption for individuals and organizations, as they may lose access to important files and systems until the ransom is paid or a solution is found to restore the data.

In short? Malicious folks use malicious tools to hold your data and/or device ransom until you pay up. Not nice. Very mean.

Ransomware now costs many billions of dollars worldwide - projected to hit $265 billion in 2031. But, believe it or not, it’s actually been around since 1989 and was first disseminated by floppy disk (lol).

So, how did we get here? And how can you prevent it? Let’s find out together!

Ransomware Definitions & Terminologies

Before we dig into the evolution of ransomware, let’s quickly go over some key terms. It’s helpful to have a base understanding of these concepts to understand the intricacies of the growth and widespread impact of ransomware. If you are already familiar, I won’t get mad if you skip this part.

Types of Ransomware

Here are three of the main ways ransomware threats are executed.

Encrypting Ransomware

A type of malware that encrypts the victim's files, making them inaccessible, and then demands a ransom to be paid to restore access to the files. The encryption process typically uses a strong encryption algorithm that makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to decrypt the files without the attacker's decryption key.

Scareware

Scareware is a type of malware that tricks users into believing their computer is infected with a virus or has other serious problems and then prompts them to pay for a "solution" to fix the fake problem. This type of malware is often distributed through pop-up ads, spam emails, or by exploiting vulnerabilities in software or operating systems. The "solution" offered by the malware is often malware itself, which can cause additional harm to the computer. It is also called "FakeAV" (fake anti-virus) because it often disguises itself as legitimate anti-virus software.

Screen Lockers

A type of malware that locks the victim's computer screen, preventing them from accessing their files or using their computer until a ransom is paid. The malware typically encrypts the victim's files, making them inaccessible, and then displays a message on the screen with instructions on how to pay the ransom. The message often includes a deadline by which the ransom must be paid, and threatens to delete the files or permanently lock the computer if the deadline is not met.

Types of Software & Execution

This is not an exhaustive list, but here are a few common types of software and execution used in ransomware attacks.

Virus

A computer virus is a type of malware that is designed to replicate itself and spread to other computers. It typically requires some form of user interaction, like opening an email attachment or downloading an infected file, for it to spread. Once a virus infects a computer, it can cause a range of damage, from deleting files to stealing personal information.

Worm

A type of malware that can replicate itself and spread to other computers without the need for user interaction. It typically spreads through network vulnerabilities or by exploiting security weaknesses in software. Like a virus, a worm can cause a range of damage to an infected computer and can delete files or steal personal information, but it also can spread itself quickly across networks, causing widespread harm.

Trojan

“Malware that appears to be a useful program but contains within it hidden code with destructive functions. Alternatively, the threat actor may include a “trap door” in the Trojan Horse to permit subsequent tampering…a way to get into a secured network”. (R. Rosenberg (my dad), The Social Impact of Computers, 2004, p 442)

Botnet

A botnet is a network of compromised computers known as "bots," that are controlled remotely by an attacker, known as the "botmaster." These compromised computers can be used to perform a variety of malicious actions, such as launching distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, sending spam emails, or stealing personal information.

Brute-Force Attack

A brute-force attack is a method in which an attacker uses automated software to repeatedly try different combinations of characters, words, or phrases to guess a password or other authentication credentials, and gain access to a system, account, or encryption. It is important to use strong, unique passwords and enable two-factor authentication to prevent brute-force attacks.

How Does Ransomware Spread

Okay, you are now hip to ransomware lingo. But wait, how does the ransomware actually get on your device? Here are the top 5 ways:

Malspam

In order to gain access to data, threat actors spam as many people as possible via email, with the use of malicious links or attachments to trick recipients into providing access to their data and device. These are often generic and not as targeted, compared to Phishing.

Phishing

Compared to malspam, phishing is a more targeted attack, in which the email sender impersonates a specific individual or entity to trick the recipient into clicking on a malicious link or attachment. For example, this could come in the form of an email from your “HR department,” asking you to complete an online survey - the email may look completely valid, but is, in fact, a threat actor impersonating a real contact.

Malvertising

Similar to malspam, malvertising takes a wide-net approach, via online ads. These ads may even appear on legitimate websites, but with just a few clicks, the victim has unknowingly downloaded malicious code.

Social Engineering

This is a term you will hear frequently these days and basically boils down to tricking people into doing things they shouldn't. Examples of social engineering include opening attachments, clicking links, or providing passwords by using psychology and manipulation on 3 the target. Phishing, malspam, and malvertising often include elements of social engineering by impersonating trusted individuals and institutions to extort money or information from a target.

Drive-By Download

A drive-by download is a sneaky type of malware attack in which a computer is infected with malicious software without the user's knowledge or consent. This often occurs when a user visits a compromised website or clicks on a malicious link, causing the malware to be automatically downloaded and installed on their computer. This type of download often targets vulnerabilities in web browsers and their plug-ins.

The History and Evolution of Ransomware

Alright, you’re all learned up on the basics, so let’s get into it. According to Comparitech, it’s estimated that in 2021, ransomware attacks cost the US alone nearly $160 billion in downtime - this doesn’t even include the actual costs to pay the ransom or recover the data!

So, how did this billion-dollar industry emerge? Let’s take a walk down memoryware lane.

Disclaimer: I can’t include everything here, so if you think I missed something major, I’m sorry.

1971 - 1988: Creeper, Brain, and The Morris Worm

These first three pieces of malware are not technically ransomware (missing that key component of holding your data hostage), but they did set the stage by highlighting system and software vulnerabilities, as well as the rapid speed of dissemination.

In 1971, Bob Thomas wrote the first known computer virus, called Creeper, based on John von Newmann’s Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata which suggested the idea of a piece of code that could reproduce and spread itself. Creeper was a benevolent little bugger - its only impact was printing the message “I’M THE CREEPER: CATCH ME IF YOU CAN” onscreen. While this virus didn’t do any damage, it proved that a piece of code could duplicate itself and move from device to device when connected via a network (in this case, ARPANET, basically one of the earliest versions of the internet).

Now, remember, before the internet as we know it now, it wasn’t that easy to access someone’s computer remotely; that’s where The Brain Virus comes in, spread by floppy disks (remember those?). In 1986, two computer programmers (Amjad and Basit Farooq Alvi) in Pakistan developed and sold a piece of medical software. This software was frequently pirated, so they developed a virus that would infect a portion (the boot sector) of the pirated disks. Homies just wanted to get paid, so the virus was pretty harmless but included a way to contact the programmers, who would then provide them with software to disinfect the impacted computer. Pay us money and we will fix things - is this starting to sound familiar? In this case, however, Amjad and Basit were kind of justified in their actions, since people were legit stealing their software.

Two years later, in 1988, The Morris Worm wiggled its way onto roughly 10% of all internet-connected computers within 24 hours of its release. This piece of malware was not designed to do harm, but its self-reproducing nature (creating multiple copies of itself on each device) brought infected computers to a standstill While he meant it as a proof of concept and a way to highlight major security flaws, the creator of the worm, Robert Morris, was convicted under the then brand new Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1985 in the US. He served three years probation, paid a fine, and is now a Professor at MIT.

1989: Welcome to the Stage... the Inventor of Ransomware!

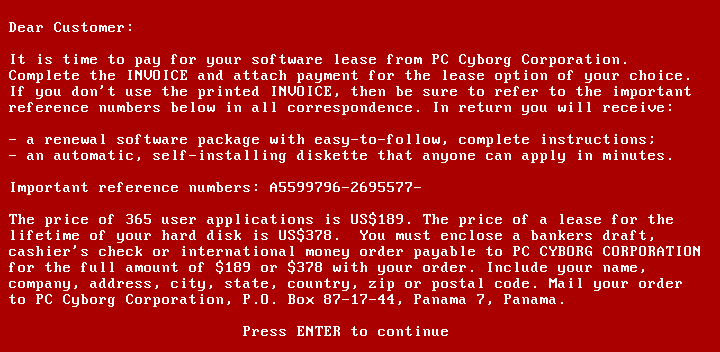

Now, this is where things start to get a little spicy - ransomware is officially born! In 1989, Joseph L. Popp, a Harvard-educated biologist, sent 20,000 floppy disks to attendees of the World Health Organization's AIDS conference. The disks were presented as containing a questionnaire to determine the risk of contracting HIV, and there was no reason to suspect any malicious intent from the accredited researcher. However, the disks actually contained malware, known as the AIDS Trojan, which encrypted victims' files and demanded payment of $189 in exchange for a decryption key.

IT specialists were able to quickly discover a decryption key, allowing victims to regain access to their files without paying the ransom. Popp likely didn’t make much money from the whole operation, given the cost to purchase and mail out the disks, but he certainly made a name for himself as the mastermind behind the first known ransomware attack, setting the stage for all that comes after.

2000s: Ransomware Makes a Comeback

It was a chill 10-15 year break before ransomware reared its ugly head again - remember the cost of mailing out those infected floppy disks? Yeah, that was not really going to be sustainable. Plus, it's challenging to manage all those money-order payments anonymously.

So, what changed? What could it possibly be? Do you have a guess…I’ll wait a few moments for you to really ponder. Still thinking? Okay, I’ll just tell you. It’s the widespread use of the internet! The information superhighway really changed the ransoming game. Forget about cargo ships and socialite babies, the 2000s are the time for ransoming that sweet sweet data.

The early days of the internet saw notable ransomware attacks, like GPCode and Archievus, where the attackers focused on targeting multiple victims and asking for low ransom fees.

GPCode, which emerged in 2004, infected systems through malicious website links and phishing emails, using a custom encryption algorithm to encrypt files on Windows systems. The ransom demand was as low as $20 for a decryption key, which was easily crackable.

By 2006, Archievus was the first strain to use advanced 1,024-bit RSA encryption, but it failed to use different passwords for each infected system, which allowed victims to unlock their systems and led to the undoing of the Archiveus ransomware. *Queue the world's smallest violin*.

Both GPCode and Archievus were groundbreaking for their time, but are considered simplistic compared to what comes next.

2010 - 2013: Ransomware-as-a-Service and Crypto Currency Enter the Chat

Ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) is a business model in which cybercriminals can purchase and use ransomware on a subscription or pay-per-use basis, without having to develop or maintain the malware themselves. RaaS providers typically offer a variety of services, such as technical support, customer service, and even marketing materials to help their customers successfully deploy the ransomware and extract ransoms from victims. This business model has made it easier for individuals or groups with limited technical skills to participate in the ransomware market, leading to a stark increase in the number and frequency of ransomware attacks.

In 2012, Reveton (a Trojan) emerged as the first RaaS. It displayed a fake law enforcement message that accused targets/victims of committing a crime that would result in jail time if the ransom was not paid. It was also the first 'crypto-ransomware,' demanding payment in Bitcoin – this transition to cryptocurrency allowed for threat actors to receive ransom payments "anonymously" (nowadays, it is a bit easier to track ledger payments to source wallets - but still considerably more difficult than tracking bank transactions). Truly, a revolutionary game changer.

Then, in 2013, CryptoLocker moseyed onto the scene. This 'locker ransomware' locked users out of their devices using 2,048-bit encryption (the most sophisticated yet!) and was spread via email attachments. The criminals behind this came away with $27 million in ransoms in the first two months. Thick stacks.

2014 - 2015: Linux and Mobile and Macs, Oh My!

Until this point in time, most ransomware targeted PCs due to the large market share, aka SO MANY POTENTIAL VICTIMS. By 2014, cybercriminals realized they were leaving a lot of cash on the table and turned their view to Mac, Linux, and mobile devices.

2014’s SimpleLocker was the first ransomware to target Android devices, encrypting files on the device’s SD card. A year later, LockerPin (man, these names are starting to get a little unoriginal, no?) also targeted Android but functioned by locking users out of their devices by changing the PIN. This crew also released the first ransomware to target Linux users.

Fusob was another major mobile ransomware family that used scare tactics to extort victims into paying a ransom, typically between $100 and $200 (US), by pretending to be an accusatory authority and suggesting payment through iTunes gift cards. The malware infects devices by disguising itself as a pornographic video player, tricking victims into downloading it. Between April 2015 and March 2016, it accounted for 56% of mobile ransomware cases. Interestingly, upon installation, Fusob first checked the device's language: if Russian or certain Eastern European languages were used, Fusob did nothing… naturally, this kindness was not extended to the rest of the world.

2016- 2018: Ransomware Goes Mainstream

To be honest, 2016 is kind of the year that ransomware really popped off, with an estimated 638 million attacks, up from 3.8 million in 2015; that’s (checks math) more than 167 times the number of attacks!

In 2016, Petya was a new type of ransomware that took a different approach to encryption. Instead of encrypting individual files, Petya overwrote the master boot record and encrypted the master file table, effectively locking victims out of their hard drives. It did so more quickly than traditional ransomware, which made it all the more dangerous.

Just three months later, another variant, Zcryptor, emerged that blended the characteristics of ransomware with those of a worm, resulting in a new type of threat called a "cryptoworm," or "ransomworm." This combination was particularly dangerous because it could discreetly replicate itself across an entire system, network, and any connected devices.

2017 saw the emergence of the now-infamous WannaCry Ransomware. This ransomware exploited the EternalBlue vulnerability in Microsoft Windows which had been developed by the US National Security Agency. It was leaked by the hacker group ShadowBrokers just a month before the attack. Microsoft had released a security patch to address the vulnerability, but not before the ransomware infected an estimated 230,000 computers in over 150 countries in just a few hours, resulting in some serious $$damage$$ to the UK’s National Health Service.

Also in 2017, a new version of Petya, cunningly named NotPetya, was used in a cyber attack in Ukraine. Like WannaCry, it used a similar method of infiltration, but the encryption it used was permanent and irreversible, making it impossible for victims to recover their files even if they paid the ransom. It even incorporated new wiper features that could delete and destroy users' files.

Then, in 2018, Ryuk popped onto the scene. Unlike other malware, Ryuk did not immediately begin encrypting files once it had infiltrated a victim's system. Instead, it spread through the system for a few days before starting to encrypt files, to cause as much damage as possible. Additionally, Ryuk disabled the Windows System Restore feature, making reverting to a previous, uninfected version of the system impossible. This bad boy is responsible for one of the biggest ransomware attacks of all time, causing millions in damages to the Universal Health Service in the U.S.

2019 - 2022: No Sign of Stopping

Cl0p popped up in 2019, becoming increasingly prevalent in the years following, and is still considered one of the top malware threats of 2023. Cl0p not only prevents victims from accessing their data but also allows attackers to steal that data. Technical details of the malware have been analyzed by McAfee and it has been found that it can evade security software, making it a dangerous threat to victims. So, not only do these threat actors hold your data hostage, they can steal it too - a particularly scary proposition for major institutions that hold personal/classified data.

Cl0p ransomware has evolved to target entire networks, rather than just individual devices. It has been known to cause significant damage, even to large organizations. A notable example is the Maastricht University in the Netherlands, where almost all Windows devices on the university’s network were encrypted using Cl0p, and a ransom was demanded the decryption of the files.

Also emerging in 2019, REvil, also known as Sodinokibi, is a form of crypto-ransomware created by the REvil cybercrime group, based in Russia. The group primarily uses phishing tactics to spread the malware, but it is known to use brute-force attacks to target high-profile victims as well. The group has mainly targeted companies in the US and Europe, avoiding attacks on companies from countries that were previously part of the Soviet Union.

Then, in 2020, Maze Cartel was developed by a few different independent threat actors coming together to create something they could all be proud of. It has since been adopted and utilized by multiple attackers for extortion purposes. Much like Cl0p, Maze not only encrypts the data but also makes copies of it and threatens to publicly release the data if the ransom is not paid. We call this the ol' double extortion. It also double sucks for the victims.

Another ransomware, BlackCat, had successfully targeted and breached at least 60 organizations worldwide as of March 2022. It is noteworthy for being the first professional ransomware coded in Rust, a programming language known for its security and ability to handle concurrent processing. A big strength is Rust's cross-platform capabilities, enabling attackers to adapt the malware to various operating systems, like Windows or Linux.

Folks, there’s more. Way more. But honestly, we have to move on now.

The Biggest Attack to Date

It can be a little tricky classifying “Biggest Attacks” - are we talking about the biggest ransom payouts? Most estimated damage by dollar value? Most personal damage? Well, for our purposes, it’s a little from column A, a little from column B, a little... you get the point. Here are a few major ransomware attacks that made the headlines over the last few years.

Colonial Pipeline (U.S.) - $4.4 Million Ransom Paid in Bitcoin

In 2021, a group of hackers known as DarkSide utilized a variant of the REvil malware in an attack on the Colonial Pipeline, an oil pipeline system. This marks an increase in the number of cyber attacks on critical infrastructure. The pipeline was forced to shut down temporarily, causing a disruption in the East Coast fuel supply. Colonial Pipeline quickly paid a ransom of $4.4 million in Bitcoin. The FBI later was able to track down and recover a portion of the ransom money.

Universal Health Services (U.S.) - $67 Million in Damages

In September 2020, a significant ransomware attack occurred at Universal Health Services (UHS), causing over $67 million in damages (before taxes). UHS chose not to pay the ransom and instead worked with internal and external security experts to regain access to its systems and data. The malware used in the attack was Ryuk, which, by design, had spent several days spreading through the system before beginning to encrypt files.

National Health Service (NHS) (UK) - £92 Million in Damages

In 2017, WannaCry ransomware was able to infiltrate multiple National Health Service (NHS) systems in England and Scotland, causing significant disruptions. Even though the NHS did not pay the ransom, the estimated cost was a loss of £92 million. The cyber attack was stopped by a fortuitous discovery of a kill switch by Marcus Hutchins, a computer security researcher, who registered a domain that the ransomware was programmed to check. In the following week, the kill switch became a target for powerful botnets attempting to take the domain offline, intending to cause another outbreak.

CNA Financial (U.S.) - $40 Million Ransom Paid

In March 2021, CNA Financial experienced a ransomware attack that resulted in the encryption of around 15,000 of its systems. The attack started when an employee inadvertently downloaded a fake browser update from a legitimate website, which was carrying a strain of the Phoenix CryptoLocker ransomware. This allowed the attackers to gain access credentials to CNA's system, spreading laterally through their network. The ransom was set at a record-breaking $40 million at the time (a record that still stands today).

While it is generally advised by experts and law enforcement not to pay the ransom, CNA Financial felt that it had no other choice, as the attack had disabled a significant portion of its IT infrastructure, and paying the ransom seemed to be the quickest way to restore the system.

Who is a Target for Ransomware?

So, who are the most likely targets of a ransomware attack? The short answer: everyone is a potential target. Of course, threat actors are working to make that money, so they tend to look for specific high-value victims for their attacks:

Healthcare Organizations

Hospitals and healthcare providers are popular targets for ransomware attacks because they often have sensitive patient information that attackers can threaten to release if the ransom is not paid. Additionally, healthcare organizations are often seen as "essential" services, and so they may be more likely to pay a ransom to quickly restore access to critical systems and patient data.

Local Governments

Many cities and municipalities are popular victims of ransomware attacks because they often have limited resources to devote to cybersecurity and may not have the expertise or funds to recover from an attack without paying a ransom.

Educational Institutions

Schools and universities store sensitive information about students and staff and may have a limited budget for cybersecurity. The attackers may take advantage of this and threaten to release sensitive data if the ransom is not paid.

Key Industry Businesses

Businesses in key industries such as finance, energy, and manufacturing are popular targets because they often have critical infrastructure and operations that cannot afford to be shut down for long periods. Attackers know that these organizations may be more likely to pay a ransom to quickly restore access to their systems.

The common threads in these popular targets for ransomware attacks are that they are perceived to have the ability to pay a ransom and the potential for significant disruption if the systems are shut down.

How to Protect Against Ransomware

Alright, are you scared yet? Convinced it’s only a matter of time before you are a victim of a ransomware attack? Well, fear not, there are simple, common-sense steps you can take to protect yourself and your business.

Be Cautious Opening Links, Emails, & Attachments

Be cautious with email/text attachments and links, especially if you are not familiar with the sender or the email looks suspicious. This is one of the most essential steps in protecting yourself and your data - its importance cannot be overstated. Over in support land, we have strict rules about this: we only accept certain types of email attachments (the kind that can’t secretly include malicious files) and we do not click on links from users.

Use Two-Factor Authentication (2FA)

Use two-factor authentication (2FA) wherever possible to add an extra layer of security to your online accounts. This one is an easy win and should be done whenever possible. While you are at it, make sure you are using super secure passwords and not re-using any passwords across different accounts. Now would be a great time to check if any of your passwords have been compromised.

Regularly Update Software

Regularly update all software and operating systems to ensure that the latest security patches are installed. This can help prevent attackers from exploiting known vulnerabilities.

Regularly Back Up Your Data

Regularly back up important data to an external storage device, cloud storage, or another location. This can help you restore your files in case of an attack.

Restrict Access to Sensitive Data

Limit access to sensitive systems and data to only those who need it, and use network segmentation to limit the potential spread of malware.

Train Your Employees

Train employees on how to identify and avoid phishing emails and other social engineering tactics, along with other general best security practices.

Have a Response Plan

Have an incident response plan in place, including steps to take in case of an attack - and practice them regularly. If your data is compromised, you don’t want to be wasting time figuring out what to do next. Stay alert, people!

You may have noticed we haven’t suggested an antivirus program. Obviously, you do you, but we don’t recommend the use of one at all. More often than not these "security suites" cause more harm than good. Following the common sense tips above are really your best bet for staying safe. But don’t just take our word for it.

VPN and DNS Services Help Keep You Protected

Of course, I have to mention Windscribe (our kick-ass VPN service) and Control D (our hot-as-shit SmartDNS service).

Both services allow you to enable our dynamic Malware blocklists so that sites known to distribute malware, launch phishing attacks, and botnet command-and-control servers are blocked at a DNS level. That means that they are blocked before your computer can even connect to them, drastically reducing the probability of infection.

Now you can go out armed with knowledge and be able to protect yourself from the Pirates of the Internet!